qathet Living, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Lee George stands on the bank of the Tla’amin Creek, his baseball cap dampening in the light July rain. The ground he stands on is muddy. He scans the river, looking for coho fry.

Just a few inches of water flow

over the rocky creek.

A few tiny fish swim by.

Lee, who has managed this hatchery since about 1990, is worried about the level of the water, the heat. What will it do to this year’s salmon?

A month later, in September, Tla’amin Hegus John Hackett confirmed that the Nation bought 900 salmon at the end of the summer. These fish went to the Elders. He also explained that administration is working on finding alternatives to traditional foods to help save the salmon, while keeping our culture alive.

With the Fraser Valley salmon numbers much lower than they should be, how is the qathet Region’s fish count in comparison?

Here, this summer’s extraordinary heat waves meant Lee, as well as hatchery operators Leonard Harry and Vern Wilson, were worried about salmon fry dying in the river. Lee says that as of August 20, Tla’amin Nation was asked to comply with the province-wide closure of fisheries to help boost the sockeye numbers. Tla’amin agreed.

However, even with slightly higher numbers of salmon returning, compared to last year, the province will continue to protect the salmon by limiting commercial fishing. Even Tla’amin is continuing to prohibit catching sockeye for food, ceremonial and social purposes.

It wasn’t just the heat wave, explains hatchery manager Lee.

“Over the years, numbers of fish have been declining due to overfishing of commercial herring and sockeye fisheries,” he says. “We are also dealing with other issues on top of overfishing, like climate change. Low water flows and high water temperatures are the fishes’ worst enemies.

“When the water warms up, it dilutes the oxygen and creates fungus leading to sickness in the salmon, resulting in them dying off before being able to spawn their eggs.

“We have to think outside the box and ask ourselves what do the salmon need in order to multiply. Clean, healthy, cool water. No pollution. No disruption for returning salmon. And control of the access to the commercial fisheries.”

The Fraser River estuary – where the ocean connects to the river – is surrounded by new industrial sites, creating more and more problems for the salmon returning each year.

Current law claims to prioritize escapement of salmon to spawn before anything else, but Lee says it doesn’t deliver. “They have been doing this backwards for years. This allows a commercial fish before salmon have reached their spawning streams. Someone needs to rewrite the book on declining salmon in British Columbia and send it to the fisheries minister.”

Indeed, there is hope, and it’s local.

Shortly after the salmon commissions’ announcement that sockeye returns are shockingly low, Tla’amin Nation released its new Watershed Protection Plan. Watersheds are areas of land that drain surface and groundwater into another body of water such as a river or ocean.

This plan will look to protect watershed health, for drinking water quality, but also for the aquatic habitats that are home to fish and provide for other creatures. The hope is for this to become a living document, so that it can continue to be planned, to suit whatever needs the watersheds are depending on.

A couple of these now-protected local watershed areas are Theodosia River and Powell River. Once home to Tla’amin villages, these rivers housed millions of spawning salmon. However, dams have been built on both of these areas, and because of that, the salmon returns have rapidly declined each year.

Dams mean less water flowing, which is too warm, and of poor quality, so fewer fish can thrive.

The watershed protection will help protect salmon and other aquatic life, and will cover all Tla’amin treaty lands. Hopefully, this will help boost salmon and other fish populations.

What are the biggest challenges the fish are facing?

The challenges are laid out in Tla’amin’s March 2021 Watershed Protection Plan.

- 1. Water temperature is increasing each year. This decreases oxygen levels in the water, meaning fish have trouble “breathing.” Higher water temperatures allow diseases to take hold, killing the fish, which are then eaten by other animals that will end up getting sick too. The water temperatures also affects fish incubation, and gives juveniles a lower survival rate.

- 2. The amount of water flowing has reduced. Summer flows are much lower, fish such as Coho depend on this water flow, which is now drying up. Peak flow times are changing, meaning spawning and migration schedules are being undermined. This means fewer fish are showing up in migrations and more fish can die from predators in the ocean.

- 3. Winter floods are much more intense. Habitats in lower areas are hit badly, as sediment and garbage dirty the water, killing fish while also decreasing their eggs’ survival.

- 4. Drought conditions isolate fish. These trapped fish have less food and less water, which ultimately means fewer fish. A large portion of the province was on fire, the isolated fish in those areas have been harmed or even killed as they have nowhere else in the stream to swim to for safety.

- 5. Less snow. Southwest BC’s once-heavy snowfalls are quickly becoming heavy rains each year. The rivers that depend on the snow melt in the spring are getting less water. Ultimately, watersheds are receiving less water.

- 6. The oceans are changing. From sea levels to storm surges, warming waters to arid estuaries, the impact of climate change affects salmon, shellfish, crustaceans, and even mammals.

- 7. Overfishing, the fault of both commercial industries and the public, has had a major impact on salmon. Fishing in general creates other problems for aquatic species too. Humpback whales have been getting caught in many fishnets off of Vancouver Island and even qathet’s shores, throughout the 2021 summer. Overfishing has impacted orcas as well, who depend on the salmon as their main food source.

Local trout enthusiast Patches Demeester notes that, while salmon attract attention, wild steelhead are also in a sharp decline.

“Winter-run steelhead returns are in absolute ruins,” says Patches. “The summer-run steelhead (saltwater-going rainbow trout) are slowly falling behind in a downward curve too.”

Trout that live in rivers, he explained, rely on bugs for food. Those bug populations are dying off because of the acidification of water, or rising temperatures. Lake-living trout are impacted more slowly than river trout. Unfortunately, he says, the lakes this year suffered a massive drought due to several heatwaves, which damaged steelhead populations.

“We are seeing extremely low steelhead returns. They are on the brink of total collapse. It’s very sad.”

But Patches says there is some hope from some of the salmon he’s observed. “I’ve seen the best numbers so far for pink returns this year. And there is more undersized chinook out here than most folks have seen in years. So there are some salmon species that are in good numbers this season.”

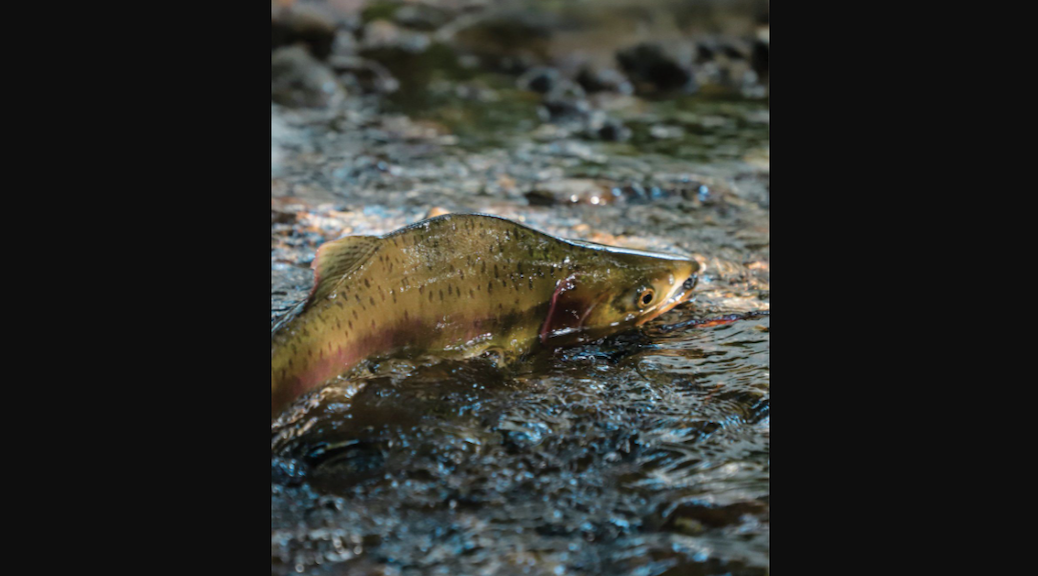

Top photo credit: Pink salmon swimming through a stream that has not received enough rain – Photo by Abby Francis

Sign-up for Cortes Currents email-out:

To receive an emailed catalogue of articles on Cortes Currents, send a (blank) email to subscribe to your desired frequency:

- Daily, (articles posted during the last 24 hours) – cortescurrents-daily+subscribe@cortes.groups.io

- Weekly Digest cortescurrents – cortescurrents-weekly+subscribe@cortes.groups.io